David Wilk interviews Robert Pennoyer about the Whiting Awards

March 30, 2016 by David

Filed under Publishing History, PublishingTalks

Publishing Talks began as a series of conversations with book industry professionals and others involved in media and technology about the future of publishing, books, and culture. As we continue to experience disruption and change in all media businesses, I’ve been talking with some of the people involved in our industry about how publishing might evolve as our culture is affected by technology and the larger context of civilization and economics.

Publishing Talks began as a series of conversations with book industry professionals and others involved in media and technology about the future of publishing, books, and culture. As we continue to experience disruption and change in all media businesses, I’ve been talking with some of the people involved in our industry about how publishing might evolve as our culture is affected by technology and the larger context of civilization and economics.

I’ve now expanded the series to include conversations that go beyond the future of publishing. I’ve talked with editors and publishers who have been innovators and leaders in independent publishing in the past and into the present, and will continue to explore the ebb and flow of writing, books, and publishing in all sorts of forms and formats, as change continues to be the one constant we can count on.

It’s my hope that these conversations can help us understand the outlines of what is happening in publishing and writing, and how we might ourselves interact with and influence the future of publishing as it unfolds.

It’s well known to all that literary writers more often than not struggle financially. This is especially true for writers early in their careers. According to most research, fewer than five per cent of writers who identify as “professional” are able to make their livings directly from writing.

Aside from the National Endowment for the Arts fellowships for writers, there are few programs that provide direct support to emerging and early career literary writers. That is why the Whiting Awards, given annually by The Whiting Foundation since 1985 have been so meaningful to literary culture, and of course, to the writers who have received this form of support.

The Whiting Foundation provides $50,000 to each of ten writers every year. Writers cannot apply for these awards–instead, Whiting accepts nominations from 100 individuals in the literary arts, and then an anonymous panel of six toils in secret throughout the year to read the work, and then argue over who should be selected based based on the criteria of early-career achievement and the promise of superior literary work to come.

Overall, more than $6.5 million has been awarded to 310 poets, fiction and nonfiction writers, and playwrights to date. This is an incredible program that has had a remarkable impact on American literature. Some of the now recognizable writers selected over the course of the last 30 years include David Foster Wallace, Colson Whitehead, Tracy K. Smith, Jeffrey Eugenides, Lydia Davis, Denis Johnson, Susan-Lori Parks, Mary Karr, Tony Kushner, Michael Cunningham, Alice McDermott, August Wilson, Jorie Graham, Mark Doty, Deborah Eisenberg, Ben Fountain, Justin Cronin, Tobias Wolff, Jonathan Franzen, Terrance Hayes, Ian Frazier, and John Jeremiah Sullivan, all of whom were “emerging” when their awards were given.

Every time I see a new list of Whiting Award winners, I feel compelled to explore their work, as I am sure I will find some whose writing will affect my imagination and attract me to continue to follow them in the future.

The recently announced 2016 winners are:

Brian Blanchfield, Nonfiction

Alice Sola Kim, Fiction

J. D. Daniels, Nonfiction

Catherine Lacey, Fiction

LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs, Poetry

Layli Long Soldier, Poetry

Madeleine George, Drama

Safiya Sinclair, Poetry

Mitchell S. Jackson, Fiction

Ocean Vuong, Poetry

So how did the Whiting Awards come about? The history of the Whiting Foundation is a fascinating story. I had the good fortune to publish the memoir of attorney Robert Pennoyer in 2015, As it Was, in which he recounts the story of the Whiting Foundation and its programs. Bob was one of the first trustees of the Whiting Foundation, as his firm had represented Flora Whiting, who was quite an amazing and brilliant woman.

As Bob writes, “In 1921, before IBM had even acquired its name, she had had the good fortune to sit next to Thomas J. Watson, Sr., at dinner. He told her, “My dear, I have a new company that’s going to be making things.” She invested in the stock when it was almost worthless and held on to it for almost fifty years. When she died, in 1970, she left $10 million to the foundation that she had established, with no restriction on how it should be used.”

At the outset, the foundation supported the humanities, but as its endowment continued to grow, it had to create some additional programs; Bob’s wife, Vicky was a poet, and she suggested that creative writers were in need of some meaningful support. The trustees agreed, and then hired Gerald Freund, who had worked with the MacArthur Foundation to establish their “genius” awards, to design a program to support emerging writers, and thus the Whiting Awards to Writers began.

I am pleased to present here my conversation with Bob Pennoyer, recorded in his office in New York City, talking about the Whiting Awards. His first-hand accounts of the history he has lived are unmatched. In fact, Bob’s book is full of such fine storytelling. Bob has been an attorney with the Patterson, Belknap law firm in New York City since 1958. Before that he served as counsel in the Defense Department (where he has the pleasure of testifying in front of Senator Joe McCarthy) and was in the US Navy during World War II.

Bob Pennoyer was president of the board of trustees of the Whiting Foundation for many years. In the 1960’s, Bob was a founder and trustee of Exodus House, a halfway house for addict rehabilitation in East Harlem and he has served as a trustee of Union Theological Seminary, Carnegie Institution in Washington, Columbia University and is currently serving as trustee of the William C. Bullitt Foundation and trustee emeritus of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Morgan Library and Museum.

“…The spirit that flows through these pages may be modest, but it is also filled with an irrepressible optimism and a faith in simple values that are both uplifting and marvelously contagious. As It Was is a lesson in a life well lived, and a tonic for dark and troubled times.”

— Scott Horton

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

The great writer Jim Harrison

Jim Harrison has passed on. Not too long ago he said “at my age you don’t think about the future because you don’t have one” but that is true only in the narrowest sense. His future is assured, because his words are still with us. I don’t think Jim really saw time as finite anyway. He was too busy experiencing life and thinking about how it felt and how to express the beauty of the world and all of us in it.

Jim Harrison has passed on. Not too long ago he said “at my age you don’t think about the future because you don’t have one” but that is true only in the narrowest sense. His future is assured, because his words are still with us. I don’t think Jim really saw time as finite anyway. He was too busy experiencing life and thinking about how it felt and how to express the beauty of the world and all of us in it.

His novels are beautifully written and always humane. He loved people, but understood their foibles, failures and ultimate transcendence. He loved the natural world as only a person who lived in it can do.

I’m not sure there are too many writers like him anymore. Nor will there be.

Though best known for his fiction and essays (and large appetites), Jim was first and foremost a poet: “in poetry our motives are utterly similar to those who made cave paintings or petroglyphs, so that studying your own work of the past is to ruminate over artifacts, each one a signal, a remnant of a knot of perceptions that brings back to life who and what you were at that time, the past texture of what has to be termed as your ‘soul life’.”

His latest book of poems is Dead Man’s Float, published by Copper Canyon Press, in which this poem is found.

February

Warm enough here in Patagonia AZ to read

the new Mandelstam outside in my underpants

which is to say he was never warm enough

except in summer and he was without paper to write

and his belly was mostly empty most of the time

like that Mexican girl I picked up on a mountain road

the other day who couldn’t stop weeping. She had slept

out two nights in a sweater in below-freezing weather.

She had been headed to Los Angeles but the coyote

took her money and abandoned her in the wilderness.

Her shoes were in pieces and her feet bleeding.

I took her to town and bought her food. She got a ride

to Nogales. She told us in Spanish that she just wanted

to go home and sleep in her own bed. That’s what Mandelstam

wanted with mother in the kitchen fixing dinner. Everyone

wants this. Mandelstam said, “To be alone is to be alive.”

“Lost and looked in the sky’s asylum eye.” “What of

her nights?” Maybe she was watched by some of the fifty

or so birds I have in the yard now. When they want to

they just fly away. I gave them my yard and lots of food.

They smile strange bird smiles. She couldn’t fly away.

Neither can I though I’ve tried a lot lately to migrate

to the Camargue on my own wings. When they are married,

Mandelstam and the Mexican girl, in heaven they’ll tell

long stories of the horrors of life on earth ending each session

by chanting his beautiful poems that we did not deserve.

David Wilk Talks with Wendy Burk of the University of Arizona Poetry Center

March 22, 2016 by David

Filed under Publishing History, PublishingTalks

Publishing Talks began as a series of conversations with book industry professionals and others involved in media and technology about the future of publishing, books, and culture. As we continue to experience disruption and change in all media businesses, I’ve been talking with some of the people involved in our industry about how publishing might evolve as our culture is affected by technology and the larger context of civilization and economics.

Publishing Talks began as a series of conversations with book industry professionals and others involved in media and technology about the future of publishing, books, and culture. As we continue to experience disruption and change in all media businesses, I’ve been talking with some of the people involved in our industry about how publishing might evolve as our culture is affected by technology and the larger context of civilization and economics.

I’ve now expanded the series to include conversations that go beyond the future of publishing. I’ve talked with editors and publishers who have been innovators and leaders in independent publishing in the past and into the present, and will continue to explore the ebb and flow of writing, books, and publishing in all sorts of forms and formats, as change continues to be the one constant we can count on.

It’s my hope that these conversations can help us understand the outlines of what is happening in publishing and writing, and how we might ourselves interact with and influence the future of publishing as it unfolds.

I first visited the University of Arizona Poetry Center more than 35 years ago, and am happy to have had the opportunity to visit this great place again a few weeks ago. The Poetry Center has thrived and grown over the years, and is now housed in a beautifully designed modern building on the campus of the university, with a spectacular poetry library, rooms for teaching, readings, and even an apartment for visiting poets. Tucson and the university are lucky to have this fantastic resource in their community.

Founded in 1960 by poet and Walgreen heiress Ruth Stephan, with the goal of connecting people to poetry “without intermediaries,” the Poetry Center has grown from a somewhat humble beginning to become an exceptionally vibrant organization, bringing poets from all over the world to the beautiful Tucson environment.

Stanley Kunitz was the first poet to read there in 1962, and since then hundreds of poets have come to Tucson to read their work and interact with the community. The Poetry Center recorded most of their readings, and having spent considerable time and energy to digitize its collection, these readings are now available online in the Voca program, a mind boggling and wonderful resource for anyone interested in the range of modern poetry.

Founder Ruth Stephan’s mission statement from 1960 is still the guiding force behind everything the Poetry Center does: “Poetry is the food of the spirit, and spirit is the instigator and flow of all revolutions.” The Poetry Center is a living archive, a place where the spirit of poetry serves its community.

The Poetry Center sponsors numerous University and community programs, including readings and lectures, classes and workshops, discussion groups, symposia, writing residencies, poets-in-the-schools, poets-in-the-prisons, contests, exhibitions, and online resources, including standards-based poetry curricula, most of which is open to the public.

In October 2016, the UA Poetry Center will feature eight world-class poets as they address Climate Change & Poetry in a series of investigative readings to address this question: what role does poetry have in envisioning, articulating, or challenging our ecological present? What role does poetry have in anticipating, shaping–or even creating–our future?

The Poetry Center has an exceptional staff, many of whom are poets and writers themselves. When I visited there, I had the great pleasure of talking to Wendy Burk, the librarian of the Poetry Center, and to look around the building. I spent a good deal of time browsing the amazing collection of books, broadsides and photographs in the library too, and since then, I have spent many enjoyable hours listening to some of the great poets included in the Voca archive.

Wendy is the author of Tree Talks: Southern Arizona (Delete Press) and the translator of Tedi López Mills’s Against the Current (Phoneme Media), both forthcoming in 2016. She is the recipient of a 2013 National Endowment for the Arts Translation Projects Fellowship and a 2015 Artist Research and Development Grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts. We talked together in her office at the UA Poetry Center.

Photos courtesy of The University of Arizona Poetry Center. Copyright Arizona Board of Regents

Robert Creeley, 1963, by LaVerne Harrell Clark

Lucille Clifton, 1975, by LaVerne Harrell Clark

Francine J. Harris and Tarfia Faizullah, 2015, by Cybele Knowles

Wendy Burk, 2015, by Cybele Knowles

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

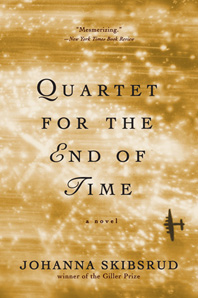

Johanna Skibsrud: Quartet for the End of Time (A Novel)

March 6, 2016 by David

Filed under Fiction, WritersCast

9780393351828 – W.W. Norton – 480 pages – paperback – ebook versions available at lower prices.

9780393351828 – W.W. Norton – 480 pages – paperback – ebook versions available at lower prices.

I’ve been interested in Canadian writer Johanna Skibsrud’s work for several years, in fact since interviewing independent publisher Andrew Steves of Gaspereau Press. The small Nova Scotia based press was the original publisher of Skibsrud’s first novel, The Sentimentalists, selected for the prestigious Giller Prize in 2010. It was a major literary event in Canada for such a tiny press to be recognized for publishing a fine novel that ultimately became a commercially successful book.

Skibsrud is a prolific and multi-talented writer. Her short story collection, This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories was published in 2011 and shortlisted for Canada’s Danuta Gleed Award. She has also published two books of poetry: Late Nights With Wild Cowboys (2008), which was shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Award for the best first book of poetry by a Canadian poet, and I Do Not Think That I Could Love a Human Being (2010), which was short-listed for the 2011 Atlantic Poetry Prize.

Skibsrud now teaches at the University of Arizona in Tucson, returning to Canada with her family every summer. Since I had the good fortune to be visiting Tucson in January, 2016, I interviewed Johanna there about her newest novel, The Quartet for the End of Time.

This book is inspired by and structured to follow Oliver Messiaen’s chamber piece of the same name (Quatuor pour la fin du temps). Messiaen’s piece was composed and first performed in 1941 while he was a prisoner of war in a German prison camp. His beautiful and haunting composition was in turn inspired by a text from the Book of Revelation:

And I saw another mighty angel come down from heaven, clothed with a cloud: and a rainbow was upon his head, and his face was as it were the sun, and his feet as pillars of fire … and he set his right foot upon the sea, and his left foot on the earth …. And the angel which I saw stand upon the sea and upon the earth lifted up his hand to heaven, and sware by him that liveth for ever and ever … that there should be time no longer: But in the days of the voice of the seventh angel, when he shall begin to sound, the mystery of God should be finished ….

Skibsrud’s novel is centered on a single moment of betrayal and how it affects the four characters whose stories are woven together during the period of the Bonus Army march and the 1930s, leading up to and then through the period of World War II.

The novel’s beginning is about Bonus Army marcher and World War I veteran Arthur Sinclair, who is falsely accused of conspiracy and then disappears. The mystery of this event will affect his son, Douglas and also Alden and Sutton Kelly, the children of a U.S. congressman who become connected to Arthur and Douglas while the marchers are camped in Washington, D.C. The book then follows these characters as they live through the period of massive social change that took place during the period leading up to and during World War II.

This novel is thoroughly compelling, beautifully written, complex in form and lyrical in language. I think Johanna has succeeded in her effort to imagine a story of loss and love through the lens of a complicated period of modern history. Tim O’Brien said this about the book, praising “…its intimate and completely compelling portraits of human beings struggling to do the right thing under ambiguous moral circumstances.”

I very much enjoyed talking with Johanna Skibsrud about this book and her work as a writer. She is as intelligent and interesting to talk to as she is to read. This interview was recorded in her office at the University of Arizona. If you want to learn more about this author’s work, I recommend visiting Johanna’s website.

And if you’re interested in the Bonus March, which is a far too little known, and truly disheartening episode of American history, you might also be interested in Georgia Lowe’s novel, The Bonus. I talked to her about this book and the Bonus March story for Writerscast in 2012.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download